When perusing the shelves, I try to think about the bigger picture. If I am buying for a friend's little girl, I think about the amount of pink, fluffy and typically 'girly' things they will be receiving this birthday, and wondering if I can combat the effects of this with the gift of building blocks. Or if I am buying books for my friend's little boy, I look through at the characters and assess the integrity of the female characters in the book. In short, it takes me a very long time to buy presents.

Recent visits to the kid's section of the book shop have caused me to leave with my head in my hands. Although there is so much work going on to raise awareness for the importance of representation in books for children, this section of the book shop is saturated with gender stereotypes and it saddens me.

Books are a way of opening up boundaries and exploring new realities for children. Books create new worlds and adventures for the reader, helping to make their most unachievable dreams into an almost tangible reality. But it seems that books aimed at boys open up different worlds than the books aimed at girls.

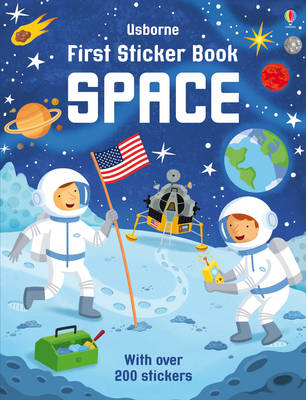

Science and space books perpetuate the idea that these realms are for boys, by rarely featuring girls or women as protagonists or even background characters. Just a short look through this section leaves me tutting in despair.

My latest search for birthday presents for my friend's children left me exasperated. It feels like despite the amount of research about the importance of considering gender roles when creating toys and books for children, representation is an afterthought.

I encourage you to look at what you are buying your children and look at who is featured in the books they are reading. Because the world those books may be opening up to them on the pages, may be reinforcing the fact that that world might not include them.

And when I say look at what you are buying, I mean really look. Even though shops are starting to stop separating their toy departments in to boys and girls sections, it can still be really obvious who the toys are designed for.

I was stopped in my tracks during one of my shopping trips by this toy display. Even though these toys don't exactly say 'boys first lab' or 'girl's first lab', you can instantly tell who these toys are aimed at.

Not only are they differentiating their science toys for different genders, but the types of science they are aiming at boys and girls is very different. The pink packaging immediately is associated with girls, and the science kits they are marketing to them involve beauty and cosmetics; because that is the kind of science girls would want to do [insert sarcasm here].

But what can we do about it? When you see example of this make sure you shout about it. Tweet it, share it and make yourself heard. Tag the publisher or campaigners like Let Toys be Toys to make it known that you are not happy about it.

But what can we do about it? When you see example of this make sure you shout about it. Tweet it, share it and make yourself heard. Tag the publisher or campaigners like Let Toys be Toys to make it known that you are not happy about it.Dr Seuess said: “The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you'll go.”

But with the gendered books content we are giving future generations, only half of the population will be going to more place - and the other half will be left behind.